做作,坐作 | On Sitting and Setting

Für die deutsche Übersetzung: HIER KLICKEN

A few months ago, as I was near the completion of a recent commission, I thought to share this with the Facebook community:

The puns came to me as I was, yes, sitting in front of my laptop for many hours at a time, battling with Sibelius (the formerly once cutting-edge notational software) to make my score look as clear and neat as possible. It was draining, brutal, yet necessary: the premiere will be in the US and I had very little time to work with the players before the concert. Nevertheless, I realized that much of the session time was spent on fixing, positioning things on the digital paper, rather than “writing more music,” as some would understand composition to be about.

Of course, using a lot of energy and time playing with the software can be a killjoy, and also a hindrance to the creative flow, as some of my colleagues have complained. I have sometimes found it discouraging, that when I finally sit down in front of my computer to input an idea, to find myself only taking care of the logistics of the notation before having to retire. “The piece needs to go on!” I say, yet unable to top tinkering with the spacing between the staves, and the spacing between notes, which were joggled yet again by Sibelius’ wonderful feature known as “magnetic layout.” (It is not a bug, I promise!).

In fact, my compositional thoughts are often formulated when I am not near my computer, a piece of paper, or any writing utensil, for it is often in my inner ear that I find quiet for the creative process: when I am sitting in the train, unable to sleep on the airplane, or waiting by the tracks for the “Delayed Bahn.” I imagine, that I am not alone in any of this? There is perhaps relief in the freedom of not having to commit anything to paper, to be free to wander in our brooding. Yet, there is greater joy when I have found the sound I have been longing to share with others.With the desire to share that which is trapped in me, of course, comes the problem of notation, whose struggling nature credits it a formidable place in

With the desire to share that which is trapped in me, of course, comes the problem of notation, whose struggling nature credits it a formidable place in compositional process. It is a basic-yet-crucial aspect; some even say, a(n) (un)necessary evil. I find it to be fascinating, that the slightest difference in positioning can often change the tone, and even the semantics of a piece. Surely, musicologists have argued heatedly over the placement of accents in Schubert piano works? To a noble end, of course…! These small, labor-intensive items signal great differences of nuances, to which we often endear ourselves to in the music that we find ourselves returning to again and again, listening after listening.

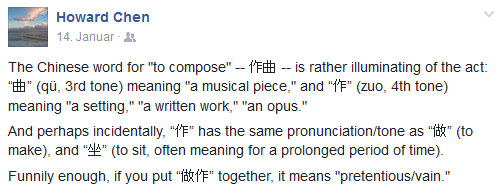

I was curious as to why the Chinese language did not use 做曲 (literally, make music) to translate the act of composing. Or is the act of making music only reserved for performers? (Or is there a deprecating joke in there somewhere?). Rather, it uses 作曲, which seems almost ungrammatical if we break it down thusly: 作 is a noun, meaning a purposeful work, an opus, 曲, also a noun, meaning a set piece of music. Nevertheless, what about 坐曲? To sit to set into music?

The word 坐 (to sit) can also mean “to stay” in its usage. Chinese people often say to one another: 坐坐坐—sit, sit, sit—as they welcome others into their home. While the phrase earnestly asks the other person to take a seat, the semantics pleads that they would stay a while longer. For this reason, saying goodbye between two Chinese friends can sometimes last an hour, and awkwardly at the door, no less…

Likewise, 坐曲can perhaps take on a similar meaning. To stay on the music, to stay with the music, to stay in the music, to stay in front of your work as you sit there laboring away at it, meditating, listening, hearing, refining, and therefore, bringing forth something of purpose—to 作曲. Is that not more exciting than to only make—to manufacture something—even when that is done with the conceit that one is supposedly creating new things? “There are no new sounds, but always new ways of listening.” (Lachenmann)

And so will I gladly sit here, there, wherever I might be, while I set my music to pieces, and pieces to a musical work!

Für die deutsche Übersetzung: HIER KLICKEN

Neueste Kommentare